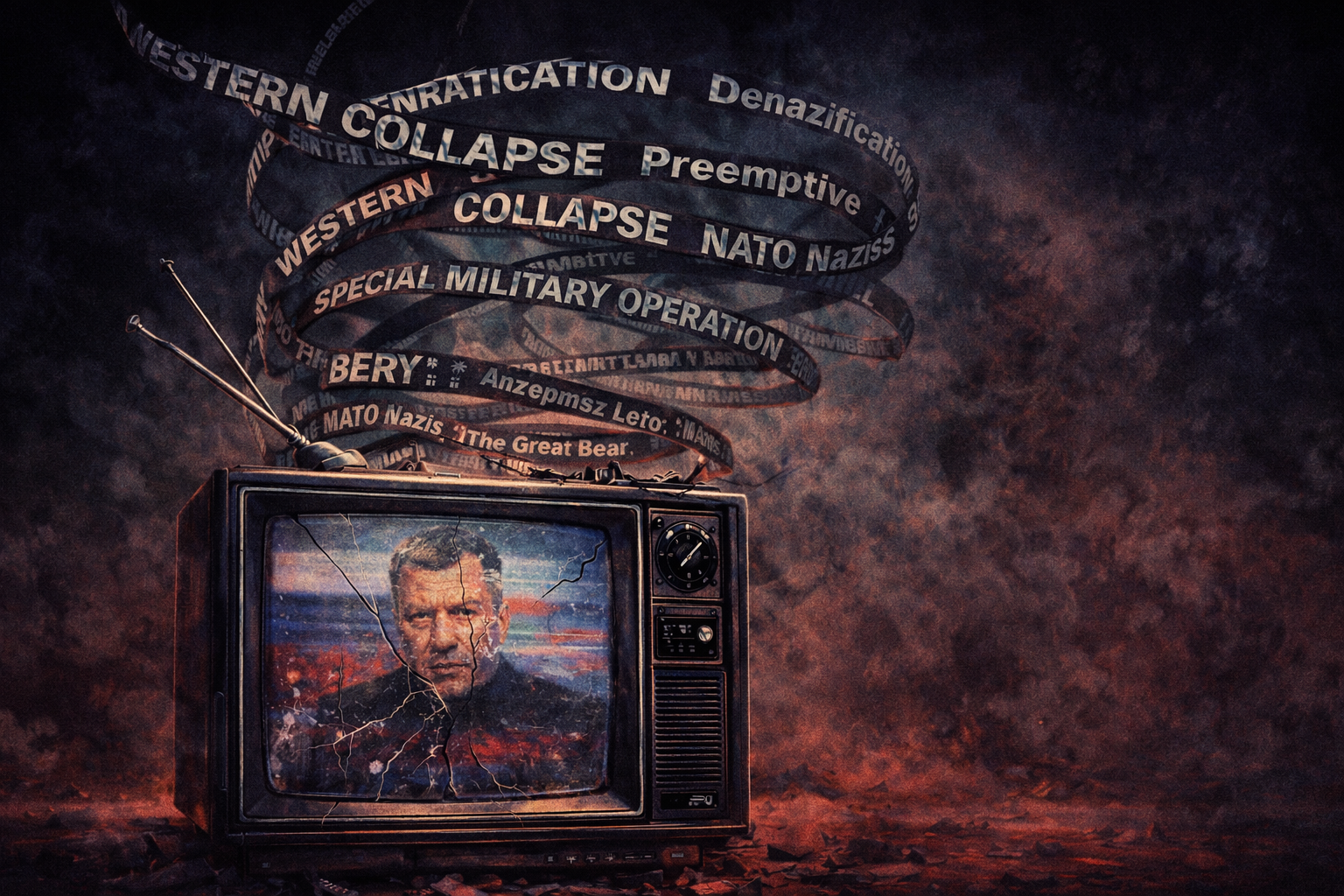

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion, its information campaign was rehearsed. The language was already there. “Special Military Operation.” “Pre-emptive defence.” “Nazis.” “NATO.” The phrases arrived fully formed, as if they’d been waiting for a signal. It had decades of posturing that the Great Bear was beleaguered by the West, and it became tanks and infantry at the Gates of Kyiv. This document will trace the Kremlin’s shifting propaganda from triumphalism to damage control and explain why it matters for negotiations.

Four years on, the story that had boasted of “denazification,” Western collapse, and Russian superiority has deteriorated into something far more defensive.

It has become a damage limitation in the face of strategic failure. Russia’s propaganda universe now looks less monolithic, less confident, and far more fragile than it did in 2022.

Putin had demanded the entire capture of the Donbas by 2023, then 2024, then 2025. As Russia now struggles to deliver the victories it promised, this system is shifting into its most aggressive phase yet. Not to win the war, but to explain why it hasn’t. This is how we got here:

Phase 1: Establish the Lie

In the opening days of the invasion, Russian state media and official discourse were dominated by familiar themes. The war was never called a war. It was framed instead as a “Special Military Operation”. This was not, they insisted, an act of aggression, but a necessary intervention to protect ethnic Russians, to “denazify” Ukraine, and to pre-empt Western threats. It was a rhetorical sleight of hand the Kremlin had used before: recasting offensive war as a defensive necessity against a hostile West or NATO.

The Russian approach is to then bombard that manufactured “reality” everywhere it possibly can. It is volume over truth. The goal is not to persuade through evidence, but to overwhelm through repetition.

This messaging dominated Russian television, websites, and state-controlled social media ecosystems in 2022. Some participants played along knowingly; others simply took the money being offered and asked a few questions.

Phase 2: Exploit the Western Bloggosphere

Scandal upon scandal has now been uncovered, over Russian covert funding and influence operations in the social media and commentariat spheres. The amount of money sloshing through this ecosystem was staggering. These sums are offered by Russian state-linked actors to social media figures, especially in the United States – after all, American clout is most sought after.

The amounts these Kremlin-backed actors can offer are astronomical compared to what independent voices could earn. So they take the money. And a pro-Kremlin line slowly but surely enters the alternative media space. From there, it is but a short hop to those narratives entering established media.

But it is not just those that are bankrolled that deepen the issue. And this is where the alternative media space faces a brewing crisis. A minority repeat these Russian talking points not out of a sense of paid-off loyalty, or genuine belief in the cause. They do so to satisfy an urge for notoriety and a few extra likes. The broader effect? Russian disinformation riddles through the websites we click through every day.

Phase 3: The First Ruptures – Reality Abuts “Reality”

For a brief period, this ecosystem appeared coherent. There was a sense, at least among its own participants, that a counter-narrative to Western reporting was taking shape, but that illusion did not survive first contact with reality.

In the modern information war, all that is needed are platforms, audiences, and enough plausible deniability to claim independence, while consistently pushing narratives that benefit a hostile state, often hidden behind appeals to “free speech.” Sound familiar? And the effect is catastrophic: it blurs reality, corrodes trust, and gives top-line cover for aggression without ever crossing a border.

However, this information space has since suffered a rapid decline. In the first year of the war, some Western voices framed Russia’s invasion as either a historical “correction” or understandable Russian “security concerns.” For a while, they found an audience among those looking for contrarian takes. But that credibility evaporated the longer the war has dragged on. Russia’s failure to equal its bombastic bravado on the battlefield undermined its bankrolled supporters.

I saw that collapse up close in captivity in Makivka, after I was taken prisoner of war defending Mariupol. Even among prisoners with no access to independent media, the gap between what Russian television and radio claimed and what was actually happening became impossible to ignore.

State broadcasts spoke confidently about Ukrainian defeats and Russian control, but both guards and inmates, who had relatives at the front, knew that the front line was moving in the opposite direction at that time. News travelled the old-fashioned way. Through whispers. Through fragments of conversations. Through the arrival and departure of the wounded. When Makivka was mentioned on television, the reactions were not pride or confidence, but disbelief. Even Russians were openly saying the reports were nonsense.

Phase 4: Information’s Counter-Strike

Independent reporting from Ukrainian front-line journalists, combined with the relentless work of OSINT communities, began to paint a far less forgiving picture: a battlefield reality at odds with the carefully curated narratives coming out of Moscow.

As Russian losses mounted and stories of corruption, mismanagement, and chaotic retreats became impossible to ignore, the legitimacy of those Western commentators collapsed with them. Even in alternative media spaces that had once been receptive to their arguments, they were no longer treated as brave dissenters. Audiences woke up to the blazing reality before them: the gap between what was being sold and what was real was too wide to bridge. Russian bravado simply could not be believed when its Great Army was bogged down around Donetsk, suffering staggering casualties.

Phase 5 – Russia’s Information Environment Crumbles

At the same time, Russia’s own information environment began to fracture. State television, nationalist influencers, and an increasingly restless cast of mil-bloggers started telling different and often conflicting stories about the war.

Figures such as Igor Girkin (Strelkov), once a central cheerleader of the invasion, began openly attacking the competence of the military and political leadership. Channels linked to Semyon Pegov of WarGonzo, Yuri Podolyaka and Mikhail Zvinchuk of the Rybar project, Alexander Khodakovsky, and Zakhar Prilepin all pushed their own versions of events, often at odds with the sanitized line on state television.

Others, including commentators operating under brands like “Kalashnikov” and similar nationalist platforms, joined a growing chorus airing grievances about logistics, leadership failures, and strategic drift.

In that splintered landscape, Western-accented apologists found themselves with no coherent narrative left to sell.

There was no longer a single, confident Russian storyline to amplify, only competing excuses, shifting goalposts, and visible frustration. The old discipline of message control had given way to a noisy, public argument about who was to blame and why promised victories had not materialized.

This was not a sudden or unprecedented development. The clearest early warning came with Yevgeny Prigozhin and the Wagner Group. For months before his mutiny, Prigozhin used social media and video statements to attack Russia’s military leadership, accusing them of corruption, incompetence, and lying about the war. These were not whispered criticisms. They were broadcast to millions. When Wagner forces marched on Rostov and towards Moscow, it was not just a military crisis; it was a public collapse of narrative discipline. A moment when the Kremlin’s information hierarchy visibly cracked.

Since then, those cracks have only been papered over. Prigozhin’s rise and fall exposed something fundamental about modern Russian propaganda: it is not a seamless machine, but a collection of competing power centres, egos, and audiences, held together by fear and convenience rather than coherence.

The infighting now playing out across Telegram and nationalist media is not an anomaly. It is the extension of a pattern he made impossible to ignore.

So, 2026?

What we are left with is no longer triumphalist propaganda, but damage control and that matters.

Despite repeated offensives and costly mobilization drives, territorial change slowed to a crawl, measured in metres, not kilometres. Nothing resembling the sweeping victories once promised on Russian television materialized. Those early clips of pundits predicting a victory parade down Khreshchatyk in three days now circulate online as dark satire, a reminder of how far the narrative has fallen.

That reality has forced a shift in tone. The language of conquest gave way to the language of consolidation. Where early propaganda spoke of historic missions and rapid victory, later messaging focused on endurance, on “holding the line,” and on managing expectations.

Regimes that move from selling victory to justifying endurance are not preparing their public for success; they are preparing them for compromise. That is the position that we are in 2026. And that is a massive strategic weakness when walking into any negotiating room.

If (and it’s a big if) Putin does sign some form of negotiated settlement, it will not be because his objectives were met, but because the gap between what he promised and what is possible has become too large to hide.